|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are four common types of simple craniosynostosis (synostosis is a general term meaning “fused bones”), with each type of craniosynostosis being caused by a different skull suture abnormally fusing shut. Following this general overview these four types of synostosis (sagittal, coronal, metopic and lambdoid) are discussed individually and then the various ways surgeons treat craniosynostosis are reviewed. To begin with, it is necessary to first determine if a child actually has craniosynostosis. This is because the most common cause for an abnormal skull shape is not craniosynostosis, but is positional plagiocephaly, caused by outside forces deforming the skull. Positional, or deformational, plagiocephaly is discussed elsewhere on this site (see Deformations) |

|

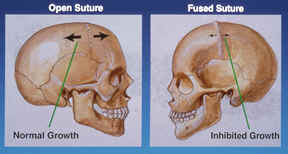

In order to better understand craniosynostosis it is helpful to know a little bit about how the skull grows. The skull is not made up of a single bone, but instead is made up of multiple different bones. The junctions where these bones meet are called sutures. We know that the skull does not grow independently; it only gets larger when the brain is growing. In the first year or two of life, the brain grows very quickly and as it enlarges it stretches the skull bones apart, with the sutures acting like expansion joints. It is believed that this stretching of the sutures results in chemical signals telling the skull to grow more bone (actually, the growth of the skull is slightly more complicated than this, and just a simplified version is being presented here). If one of these sutures has abnormally fused shut, the skull cannot expand in this region of the skull so the brain must push the other non-fused sutures further apart in order to get enough room. This combination of poor growth by the fused suture, and extra growth at the remaining open sutures, produces an abnormal skull shape that eventually becomes obvious. |

What causes sutures to fuse shut? The most common reason is probably pressure on the head while the baby is still in the uterus (womb), sufficient to cause a suture to close. We know that it is possible to cause craniosynostosis in animals by restricting the ability for the skull growth in the uterus and it is very likely that this is the primary cause for the majority of the single sutural synostoses in humans. We suspect that children born with a single sutural synostosis may have been positioned in the uterus in such a way that there is continuous pressure on a certain area of the skull that restricts the ability of the skull bones to be stretched apart by the growing brain. If the suture cannot stretch apart, it “thinks” its job is done and it fuses shut. Single suture craniosynostosis is more commonly seen in twins than in single births, further supporting this theory of in utero constraint. Certain types of craniosynostosis (metopic and sagittal) are more common in boys than girls leading some researchers to speculate that the male hormone, testosterone, might make suture closure more likely to occur. Mothers who have delivered babies with single sutural synostosis should not feel guilty that they did anything wrong during their pregnancy that might have caused this condition. Craniosynostosis occurs in spite of the mother doing everything correctly. In most instances, when children born with a single sutural craniosynostosis grow up they will not pass this trait on to their own children. However, we have seen cases of single sutural synostoses being passed from generation to generation, suggesting a possible genetic cause. It is possible to test for many of these genes with a blood test (something that we are currently doing in Dallas while the children are in surgery). However, it should be remembered that the overwhelming majority of single sutural synostoses appear to be the product of two parents with normal genes, and a mother who has normal prenatal care. For those individuals born with a single sutural synostosis that do not have a currently recognized gene mutation, the chance of passing on the condition on to their own children is estimated to be less than 2%. The chance of a couple having a second child with a single sutural synostosis is also thought to be about 2%. Finally, there are a few drugs that might be able to contribute to the development of craniosynostosis.

It is important for parents to realize that ridging on their baby’s head does not always mean that a suture is fused. Shortly after birth the sutures are often ridged, until the growing brain flattens them out. The diagnosis of craniosynostosis is usually made following some type of imaging; the simplest type being a plain x-ray. On a plain x-ray, open sutures appear as dark lines whereas fused sutures appear as white lines. However, it can sometimes be challenging to tell for sure if a suture is really open or closed; therefore, it is more common for doctors to order a CT scan. These scans are the most accurate way to tell whether or not a suture is open or closed. However, other doctors have raised questions about the long-term effects of the radiation associated with CT scans (which is a lot more than plain x-rays); specifically, the possibility that this radiation could have a negative effect on intellectual development or might lead to an increased risk for brain tumors and leukemia. These concerns are based on older studies when CT scans emitted more radiation than today, and it is likely that these tests have become safer. As it turns out, when a suture fuses shut, the resulting reduction in growth around the closed suture along with the compensatory over-growth by the remaining open sutures, produces a characteristic skull shape uniquely different for each type of craniosynostosis. We have published a study showing that a physical examination performed by a craniofacial surgeon is extremely good (98% accuracy) at diagnosing craniosynostosis as compared to CT scans (Publication #28). Therefore, at our center in Dallas, we do not routinely recommend these scans for our patients, reserving this test for those rare cases where the physical examination is uncertain.

Studies have shown that over time, pressure can build up inside of the skull in children with craniosynostosis. This risk seems to be low in the first year or two of life, but probably increases as children grow much older. The problem with pressure building up inside the skull is that once it gets high enough it can reduce blood flow to the brain. The big question is: can a single sutural synostosis have a negative effect on a child’s development or intelligence? At the current time, I believe craniosynostosis either has no impact a child’s mental development, or if it does, it cannot be measured by current testing. Although some studies have been published that suggest that children with single sutural synostosis may have a higher rate of minor developmental or behavioral problems, others suggest that this is not the case. If one performs developmental testing (or looks for behavioral issues) on a large group of children who do not have craniosynostosis, in general about 20% of all these unaffected children might normally be expected to show some problems. So, while a small percentage of children with craniosynostosis might have some developmental issues, I am not convinced that a fused suture caused these issues. We also do not know the answers to a number of other good questions such as: does surgery help to prevent developmental problems? Are there different problems specific to the different fused sutures? Is the brain less affected in those cases where the skull is less affected? It has been our experience that the vast majority of children with a single sutural synostosis are normal children who just have early closure of one of their sutures.

If one considers all that is known about brain growth and development, and then reviews all the studies examining raised intracranial pressure and blood flow to the brain, it seems pretty clear that most children do need an operation to fix their craniosynostosis. Interestingly, the purpose of surgery is not to release a restriction on growth by opening up the fused suture. This is because surgery cannot create a functioning suture. Once a suture is fused shut, no operation is able to recreate the growth center that was lost by the fusion. Instead, the operation needs to accomplish two things:

If children do not look normal it can have a profound effect on their personality, their willingness to socially interact with their peers and even their desire to go to school. The most difficult decision for surgeons and parents comes when children are only mildly affected. When the skull shape is only minimally different from normal it would seem less likely that there could be any significant effects on the brain. In these instances, we may recommend not operating right away and just following the child conservatively while they are growing; saving surgery for only if the shape gets worse, or if any signs show up suggesting that pressure might be increasing inside the head. Listed below are the four major types of single sutural synostoses. For more information on the minor sutural fusions, such as squamosal and lower coronal, we recommend discussing these with your local surgeon (or, you may contact our office).

Listed below are the four types of single sutural synostoses:

|

|

Plagiocephaly is the term used to describe the shape resulting from craniosynostosis of either the right or left coronal suture. This suture runs across the top of the skull extending, roughly from ear to ear. The soft spot, or fontanel, is located at the very top of the skull, midway between these two sutures. When the coronal suture is fused, the soft spot will usually be closed. On the same side as the sutural fusion one can often see or feel a raised ridge of bone. When viewed from above, the forehead on the fused side is further back than the opposite side, which has usually slightly overgrown forward, in order to compensate for the brain’s inability to grow on the fused side. In looking directly at the child, the eyebrow is higher on the fused side, which makes the eye seem more open. Often, parents might think that the eye on the unaffected side seems abnormally closed; when actually, it is that the eye on the affected side is abnormally more open. Some may notice that their child’s nose is slightly off-center, with the top of the nose angled or pointed towards the side of the fused suture. It is common for parents to say that their child looks worse in a mirror, which may be related to the fact that a mirror flips the image around so the right side becomes the left, etc. So instead of seeing your child as you are used to, the mirror flips the flatness to the opposite side. The incidence of plagiocephaly is estimated to be about 1 in 3500 births and this condition is slightly more common in girls than in boys. Almost all children affected with plagiocephaly require surgical treatment. A small percentage of children with one coronal suture fused shut can have a gene mutation, which may signify a condition called Muenke syndrome. The treatment for plagiocephaly is discussed in the Treatment section.

|

|

|

Scaphocephaly is the term used to describe the shape that results from craniosynostosis of the sagittal suture. This suture runs from front to back starting at the fontanel (soft spot) at the top of the head and extending backwards along the middle of the skull. Often, the soft spot will be closed. A ridge can either be seen or felt running along the top of the head, in between the right and left halves of the skull. When viewed from above, the skull will be wider near the forehead but gets narrower towards the back of the skull (which is the opposite of what is normal: the back of the skull should be wider than the front). When looking straight on at the child’s face, the forehead may seem bigger, and the sides of the skull look narrow. Perhaps the most characteristic finding of sagittal synostosis is that in looking at your child from the side, the back of the skull is lower than the front, which is the opposite of what is normal, and the skull will also appear to be growing longer in the back. Most children with scaphocephaly will have very high head circumferences. This is because the skull length must grow abnormally longer, in order to compensate for the reduced width and height of the back part of the skull. The incidence of scaphocephaly is about 1 in 2,000 births. It is the most common form of craniosynostosis. Almost all children affected with scaphocephaly require surgical treatment. The treatment for this condition is discussed in the Treatment section.

|

|

|

Trigonocephaly is the term used to describe the shape that results from craniosynostosis of the metopic suture. The metopic suture extend from the top of the head, beginning at the fontanel, or soft spot, and runs down the middle of the forehead stopping just above the nose. A ridge can usually be seen running down the center of the forehead, and the forehead will appear narrower. The eyes may be spaced closer together than normal. The most characteristic finding is that when looking down from above, the forehead will have a triangular shape like the bow of a boat. The incidence of trigonocephaly is somewhere between 1 in 2,500 to 1 in 3,500 births. Trigonocephaly has been reported to occur in mothers who have taken Valproic Acid (Depakene, Depakote, and Convulex) for seizures. Not all children with metopic synostosis require treatment and sometimes it can be very difficult to determine if a child has enough forehead narrowing to require treatment. Those who are very mildly affected may not require surgery. One of the reasons why determining if surgery is necessary or not is so challenging is that this suture is different from all the other sutures; it is the only one that normally fuses shut in every child, beginning as early as just a few months of age. Therefore, an x-ray showing that this suture has closed is not all that helpful: it might just be a normal fusion. Making this more difficult is that when this suture normally closes, it can sometimes create a very prominent ridge running down the center of their forehead, without producing the triangular-shaped forehead. Children with an isolated ridge running down their foreheads do not require surgery (Publications, Book Chapters #3). Only those children who have actual trigonocephaly need treatment. In Dallas, this decision is made on a physical examination, not by a CT scan. The treatment for this condition is discussed in the Treatment section.

|

|

|

Posterior plagiocephaly is the term used to describe the skull shape that might be caused by craniosynostosis involving either one of the two lambdoid sutures. These sutures are located on the back of the skull, one on the right side and one on the left side, and they come together like an upside down “V.” Usually, only one side fuses shut; it is extremely rare that both sides will be closed. When viewed from above, the side with the fused suture is flatter than the opposite side. One sign that the lambdoid suture might be fused is the presence of a low bump (mastoid bulge) behind the ear on the same side as the fused suture. Another sign of lambdoid synostosis is that the height of the skull is lower on the flattened side. Finally, if the back of the skull seems to grow outwards on the opposite side of the flatness, a fused lambdoid suture is likely. However, if there is no reduction in skull height on the affected side, no compensatory bossing on the other side of the skull and no low mastoid bulge then a skull deformation, or positional plagiocephaly, should be suspected instead of a fused suture. It is critically important to determine whether or not a child truly has a fused suture because skull deformations never need to be surgically treated. Many children in the past have undergone unnecessary surgery for presumed lambdoid synostosis, when it turned out instead that all the child had was a deformation. Making the diagnosis even more difficult is that on plain skull x-rays, the lambdoid suture can be misdiagnosed as being fused shut, when it is actually open. The correct diagnosis of lambdoid synostosis is made either by an experienced craniofacial surgeon on examination, or by a CT scan. Children who have lambdoid synostosis do require surgery. Experienced teams will also look for a Chiari malformation in children with lambdoid synostosis by getting a MRI scan. A Chiari is when a part of the brain called the cerebellar tonsils can put pressure on the spinal cord. We have published a study showing that 60% of children treated for isolated lambdoid synostosis at our center in Dallas were found to have an associated Chiari malformation (Publication #61). When a Chiari is present, this changes the way we treat the lambdoid synostosis. The incidence of posterior plagiocephaly from a fused lambdoid suture is currently unknown but is probably around one in 50,000 births. One reason for the difficulty in estimating how often this fusion occurs is that it has probably been over-diagnosed in the past. It is certainly one of the least common types of craniosynostosis treated at craniofacial centers, and therefore this condition is probably best managed at one of the busier centers. The treatment for lambdoid synostosis is discussed in the Treatment section. .

|

Sometimes, more than one suture can fuse shut. When both coronal sutures are affected, it is more likely that the child might have a syndrome. For a good starting point, please refer to the sections on Apert, Crouzon, and Pfeiffer syndromes. There are also some even more rare conditions in which multiple sutures are fused in different combinations, sometimes referred to as complex craniosynostosis. For more information on this type of craniosynostosis you should either contact your surgeon, or you can contact our office to learn about our research on these rare presentations for craniosynostosis (Publications #27, 41) Once again, these unusual conditions are best treated at the very busiest national centers.

Children with suspected craniosynostosis will typically undergo an evaluation by a craniofacial team prior to determining if surgery is necessary, and if needed, determining the best way to treat it. When an operation is necessary, at most all major centers you can expect that your child will be treated by a craniofacial surgeon and a pediatric neurosurgeon working together as a team. Should parents meet a neurosurgeon who recommends operating without a craniofacial surgeon, or visa versa, I recommend seeking another opinion. Craniofacial surgery is the specialty with the greatest degree of expertise in treating craniosynostosis. It is the craniofacial surgeon’s role to decide which parts of the skull are to be removed, the neurosurgeon’s role to safely remove these bones, and then the craniofacial surgeon’s role to remodel and rebuild the skull.

It is a common misconception that all that needs to be done is to release the fused suture so that the brain can grow normally. Unfortunately, once a suture has fused shut, it cannot be recreated. As our understanding of suture biology has improved we have come to better understand how these growth centers function. Although a fused shut can never again function as a growth center, fortunately the other sutures will compensate. In addition, the skull is able to grow in other ways, by adding layers of bone on the outside and dissolving away the inner side. Parents are often given the false impression that it is important to operate quickly in order to release the skull fusions to enable normal growth. Not only is this incorrect, studies (some performed at our center) have shown that operations actually slow down growth and that the earlier the surgery is performed, the less well the skull will grow afterwards. We believe that operations performed too early are more likely to need second operations later in life. This means that craniofacial surgeons need to carefully assess how long it is safe to delay surgery, because the longer you wait, the better the long-term result and the less a chance that a second operation might be needed at an older age. Doing the wrong operation, not being able to get a good result, and choosing the wrong time to perform the operation, all have the potential to increase the chance that a child will need a second (or even third) operation. There are many different ways that surgeons recommend treating craniosynostosis. The following provides a brief overview of some of the more common techniques.

The earliest treatments for single sutural synostoses were strip craniectomies (one variation is called the Pi procedure). In this operation a neurosurgeon simply cuts out the fused suture and throws it away. However, studies found that these operations were not as effective as hoped. Depending upon the age of the child, sometimes the removed sections of bone would quickly grow back resulting in a minimal improvement. While in older infants the opposite occurred and the skull never grew back, leaving permanent open spaces of unprotected brain that later needed surgery to repair. From these studies we learned that strip craniectomies seldom normalize the skull shape and are more likely to require a second corrective operation later on. More recent updates on the traditional strip craniectomy procedures (i.e. endoscopic, springs or distraction devices) are described in more detail below

Recognizing that the strip craniectomies could not fully correct the abnormal skull shape, craniofacial surgeons came to realize that instead of just removing the fused suture it was best to remodel and enlarge the skull. There are many variations on remodeling techniques and it is a good idea to discuss with your surgeon, which they prefer. For example, with sagittal craniosynostosis surgeons might choose one of three remodeling options: 1. Surgery is limited to the back area of the skull near the fused suture (this is my preference; see “The Dallas Procedure”). 2. The entire skull is removed and remodeled (I think that this bigger operation slightly increases the risk for complications and actually ends up looking worse over the long-term). 3. The skull is treated with two separate operations, one on the back, and then a second one in the front (why double the risks of surgery, when the problem can be fixed with only one operation?).

Recently, a few surgical teams have gone back to performing modifications on the older strip craniectomy procedures. One update is to use an endoscope (operating through a small tube) to remove the skull off the dura (the covering of the brain). An advantage of this technique is that it can be done with a smaller scalp incision. However, disadvantages include the fact that the surgeon has a limited view of what going on during the surgery and that this operation is only able to achieve a minimal enlargement of the skull. Because the endoscopic technique does not really change the skull shape, a restrictive molding headband must be worn for up to a year after surgery, in order to force changes in shape.

Some surgeons use the term “minimally invasive” to describe this procedure. In my opinion, there is nothing “minimally invasive” about removing part of the skull in an infant, especially while looking down a tube though a tiny incision. I am concerned that “minimally invasive” is more of a marketing term to suggest that this procedure is a much safer operation. In fact, there is no data showing that using an endoscope lowers the risks of death during a craniosynostosis correction. This operation is shorter and does have less blood loss than the average center doing a remodeling procedure. However, unique complications such as dural tears, or not seeing areas that are bleeding, can occur with endoscopic surgery because the surgeons’ view is limited by having to look down a long tube to see what is going on.

Another problem with endoscopic surgery is the headband or helmet that must be worn for up to a year after the operation. These are needed because the operation does not correct the abnormal skull shape, so changes in the shape are left up to the head-banding technician, not the surgeon. This means the final result is dependent upon the skill of the technician adjusting the helmet and the ability of the parents to keep the headband on their child for the full course of treatment.

In my opinion, the most concerning thing about placing a helmet on any child with craniosynostosis is that helmets work by restricting growth, which is the exact opposite of what makes sense. With craniosynostosis it is important to enlarge the skull, not to restrict growth. This is especially true because this restriction is being done in order to try to improve the shape and appearance of the child’s head, changes that were not accomplished with surgery. The way helmets work is to keep the skull from enlarging everywhere except where the technician wants the skull to fill out. So, with nowhere to grow, the brain is forced to push out the areas that do not have contact with the helmet. Putting a helmet on a child seems similar to causing craniosynostosis, where fusion of a single suture restricts growth, forcing the other sutures to compensate. When wearing a helmet, I worry that these other sutures cannot compensate and this might raise intracranial pressure. We believe that it makes more sense to never restrict growth in a child with craniosynostosis. With remodeling operations, when the surgery is over the skull is expanded and the shape is normalized. There is no need for a helmet. This is why at our center we never recommend putting a helmet on a child with craniosynostosis. So in summary, endoscopic strip craniectomies have:

So in summary, endoscopic strip craniectomies have:

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

Another variation on the older strip craniectomy techniques involves putting springs into the skull (some surgeons prefer distraction plates). Currently, only a few surgeons in the U.S. are using metal springs. These springs are placed across the gap of bone created by removing the fused suture in order to widen the skull. Springs have been shown to be fairly effective at widening a narrow skull, but it can be hard to predict exactly how much widening will occur. One of the bigger problems with this method is that the child needs to undergo a second operation just to remove the springs. Let’s examine the advantages and disadvantages of this technique.

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

At our center the surgery to correct a single suture craniosynostosis is always performed with both a craniofacial surgeon and a pediatric neurosurgeon working together through the entire operation. We believe that having two experienced surgeons working side-by-side improves the speed and safety of the operation. In addition, only pediatric anesthesiologists with extensive craniofacial surgical experience are selected. Having the same experienced team working together day-by-day brings not just better results; it also helps to prevent serious complications.

Given that our primary focus at the Craniofacial Center is treating craniosynostosis, we have developed specific treatment protocols for each type of sutural fusion, and we routinely re-evaluate our outcomes. This has resulted in our having shorter operative times and total hospital lengths of stay for all the different major types of craniosynostosis, compared to any other center’s published data. During the operation the family is given frequent updates as to their child’s condition. A typical surgery takes just under 2 hours, although children are asleep for about four hours, total. The surgery is performed though an incision that is made from ear to ear across the top of the head, but we do not shave any hair (most centers routinely shave the head). Many years ago, I developed a wavy “zigzag” incision to replace the standard straight-line incision to make it less obvious, so when children get their hair wet, it won’t part on a straight-line scar (Publication #10). Recently, I have shortened the length of this incision, keeping it about an inch above the top of both ears, so that the scar will be even less noticeable.

The goal of the operation is to remove the areas of skull that were affected by the fused suture and to rebuild the skull into a normal enlarged shape. Studies performed at our center have shown that after surgery skull growth is not normal with a tendency for the skull to grow back the way it was (Publications #26, 32). Based on these studies we now perform slight over-corrections, which is just one of the ways we seek to reduce the chance that a future surgery might ever be needed. In order to rebuild the skull, it is necessary to hold the bones together while they heal. Although most surgeons use dissolving plates and screws, I prefer to use dissolving stitches for a number of reasons. A long time ago we discovered that when other surgeons had used metal plates and screws, with subsequent growth these plates ended up on the inside of the skull with the screws poking into the brain (Publication #12). Other studies have noted the same thing can happen with dissolving plates and screws; they too can end up inside the skull against the brain, before dissolving. While unaware of any cases in which this has caused a problem, I decided many years ago to only use dissolving stitches for holding the bones together (Publication #20). We have also found that when dissolving plates and screws have been placed on the outside of the skull, with subsequent growth they can end up covered completely by bone. Once inside the bone they never completely dissolve away, leaving a weak space inside the skull. For children that require more than one operation, these weakened areas of bone make additional skull surgery technically challenging. Finally, in a small percentage of cases, dissolving plates and screws will melt into a liquid that collects in a pocket under the skin that eventually can open up a hole and drain out. So, even though using only dissolving sutures requires advanced skills that not all surgeons have, this is what I would want for my own child.

Exactly how the skull is reconstructed varies depending upon which suture is fused. The specific techniques we use have changed considerably based on what we have learned from watching our patients grow up after surgery (in Dallas we follow patients into teenage years, when growth is complete). In particular, we have discovered that following surgery on the forehead bones, certain areas can thicken up over time, whereas other areas will not. Also, any seams between different sections of bones that were brought together during reconstruction may become visible after many years. These observations have helped us to completely change the way we reconstruct the forehead (for coronal and metopic synostoses). We believe this newer technique results in better aesthetic outcomes and a lower chance that a second repair will later be necessary (currently, our published rate of second operations for single sutural craniosynostosis is about 2%). Today, just one single piece of bone is used to reconstruct the entire forehead, so that no visible seams will show up many years later (Publication #77).

Another fairly unique aspect of how we treat craniosynostosis in Dallas is that we typically do not leave any open areas in the skull at the end of the operation. Surgeons who choose to perform variations on the older strip craniectomy procedures (such as endoscopic, springs or distraction devices) leave holes in the skull with the hopes that the body will eventually fill in these gaps. Although remodeling procedures also create bony gaps (because the skull is being enlarged), it is possible to fill in these all these gaps completely with the child’s own bone, which is something that is not possible with endoscopic strip craniectomies and spring cranioplasties. However, finding the extra bone in young children can be technically challenging, especially for less experienced surgeons. Perhaps for this reason, most surgeons do not take the time to perform this additional step. We are convinced that making sure that the skull is completely rebuilt and completely intact, without any holes left behind, helps to reduce not just the risk of a possible future brain injury, it also reduces the likelihood that a second operation might someday be necessary to repair holes left in the skull.

When the operation is over we close the scalp with dissolving stitches; we never use metal staples or non-dissolving sutures, as these can hurt when they are removed. We do not apply any bandages or head wraps and do not use any drainage tubes (these tubes hurt when they are pulled out and may actually make the recovery more complicated). While these bandages are not “wrong,” they are completely unnecessary, and children find them very uncomfortable. Instead, we just shampoo the hair and comb it over the incision. I wonder if surgeons who still wrap bandages around the head are also taking a more traditional approach to surgery itself.

Our patients typically spend just one overnight in the pediatric intensive care unit and are then transferred to the floor the following day. While most children are ready to leave the hospital 24 hours after their operation, I recommend that all my patients stay for a total of two nights in the hospital. The risks of the surgery are very small at the more experienced centers. In a published study (Publication #15), we have reported the lowest infection rate following craniosynostosis repairs. We also found that there were no infections in infants undergoing first time operations for craniosynostosis (although it is still possible).

When craniosynostosis corrections are performed on older children they tell us that they never really feel any pain. They do say that their heads feels “tight,” especially during the peak of swelling, 24-48 hours after surgery. Nevertheless, we have a policy of playing soft music in children’s’ rooms after surgery, based on a study showing that playing music relaxes children and reduces the amount of anxiety they might feel (it also reduces the amount of pain medicine required). We also no longer give children opioids, or narcotics, after surgery. We have found that giving children a variation of Tylenol and ibuprofen intravenously, instead of orally, significantly reduces the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting (Publication #58). At the most experienced centers, craniosynostosis corrections can be performed at any age, including even adults.

Let’s examine the advantages and disadvantages of the Dallas technique.

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

Surgery to correct craniosynostosis may be performed at any age, including adults. Below are some of the pros and cons of earlier vs. late surgery.

In favor of an earlier correction are a number of factors:

In favor of operating at a later age are a number of factors:

Balancing all of the above factors, it seems that the ideal time to safely correct single sutural craniosynostosis is somewhere between 11-15 months of age, depending on which suture is involved, the severity of the abnormal skull shape, and a number of other factors

It is important to discuss the specifics of any proposed operation with your craniofacial surgeon to make sure that you understand what is being done. Don’t be afraid to ask your local doctors how they will perform your child’s operation and why they choose their particular technique. For more information on what kinds of questions to ask, click on “Choosing a Doctor.” Should you decide that you want the most experienced and specialized care for your child, you can learn more by clicking on “About our Center.”

| |

|

|

Examples of a plagiocephaly (left), trigonocephaly (middle) and scaphocephaly (right) seen before surgery (above) and after (below). Jeffrey Fearon, MD, FACS, FAAP Director, The Craniofacial Center 7777 Forest Lane, Suite C-700 Dallas, Texas U.S.A. 972-566-6464

*** For those who wish to contact Dr. Fearon by e-mail, it is recommended that you add his e-mail address to your address book. Sometimes e-mail spam filters may block his response to you and there is no way for him to know that you never received his answer. If you send e-mail and do not get a response, please re-send your e-mail after adding cranio700@gmail.com to your address book, or call us by phone. |

||